By: Dr. Timothy Quinn

Chief Academic Officer and Dean of Faculty

Philosophy is no longer a required course in most schools, and few students are explicitly familiar with one of its most vital branches: epistemology – the study of how we know what we know. For thousands of years, across cultures and traditions, humans have wrestled with its questions: How do we know what we think we know? Can we ever know anything with absolute certainty? What separates belief from fact, or opinion from truth?

In an age defined by information overload and digital distortion, these ancient questions have never been more urgent. What should we trust: what we see, what we read, what we experience firsthand, or what others tell us? How do we discern fact from fabrication in a world where anyone can publish anything, anywhere, anytime and where artificial intelligence can make it all look and seem real? Schools must train students to tackle these questions head-on.

In fact, today, epistemology has taken on a new name: media literacy, and this must become a core subject in every school’s curricula. Every class, in its own way, is a class about truth. Whether it’s literature, history, or physics, each discipline holds an epistemological stance —an implicit answer to the question, “How do we know?” The problem is that we rarely make this explicit. Too often, we assume students will “pick it up” through experience, or we relegate media literacy to a side unit or special assembly. That’s not enough. We must teach epistemology deliberately and transparently, because the stakes – for our students and for democracy – have never been higher. This may mean rethinking priorities and making space in the schedule. Schools will have to cut content from other disciplines, but if students do not grapple with these fundamental questions first, much of the rest may not matter.

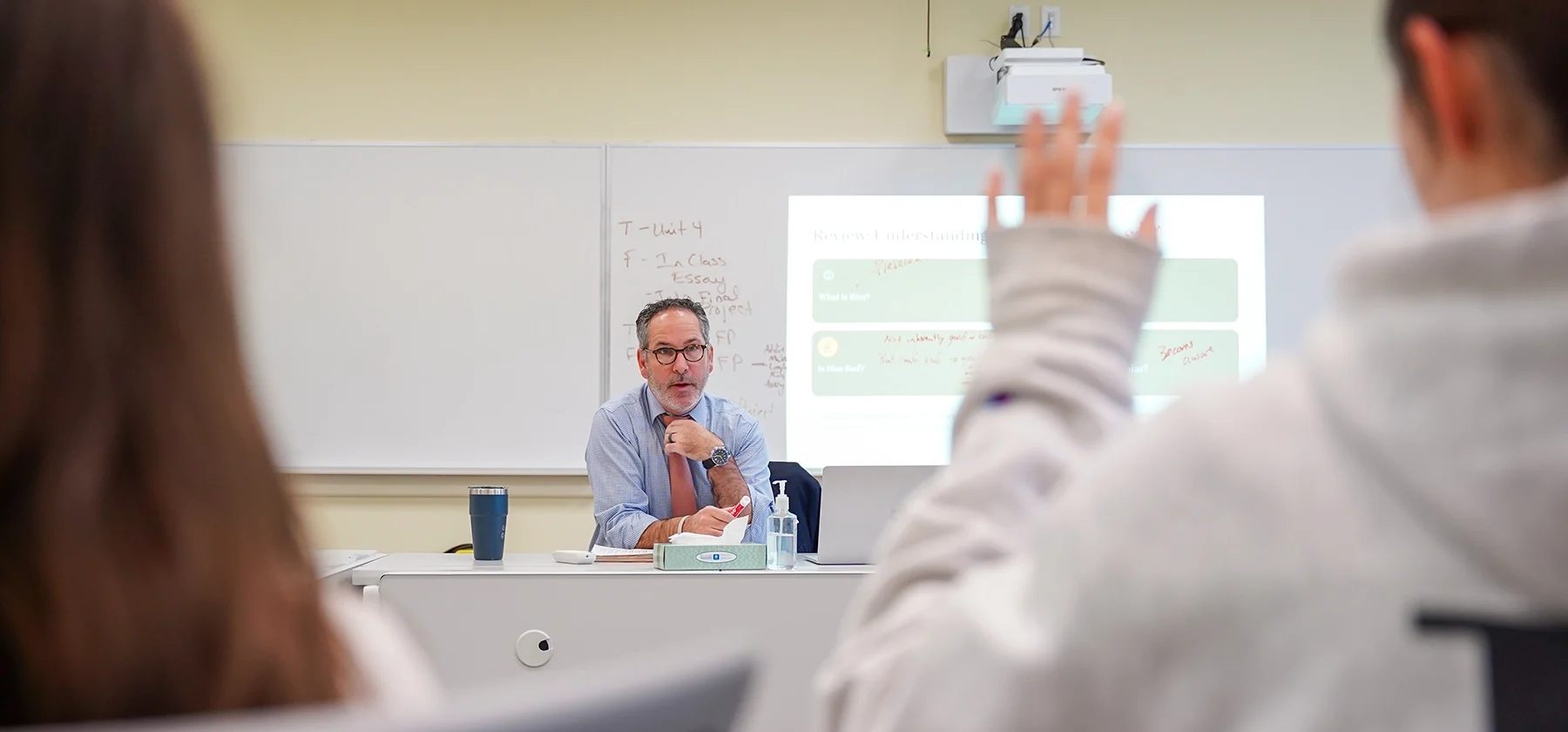

At Miss Porter’s School, this work lives most prominently in Introduction to Inquiry, a newly required ninth-grade course. The class includes four units:

- The Ways of Knowing

- The Art of Questioning

- Social Media and the News

- Cognitive Biases

We may not use the term “epistemology,” but that’s exactly what the students are studying: theories of truth and strategies for uncovering it amid both technological noise and intentional deception.

Perhaps even more importantly, the students in Introduction to Inquiry are encouraged to develop intellectual humility by coming to the realization that we all know a lot less than we think we do. Following Socrates’ example, I encourage them to cultivate and even embrace an awareness of their own ignorance. I encourage them to bring their “sword of skepticism” to every piece of information they encounter, cutting through bias, illusion, and manipulation in pursuit of truth.

In a divided world where people on both sides feel certain that they are right, the ability to say “I might be wrong” is revolutionary. Epistemology teaches humility, and humility makes empathy possible. Certainty, by contrast, too often breeds contempt, a contempt that more and more often can lead to violence.

Always a hero of mine, I have again been inspired by the skepticism of Mark Twain while reading Ron Chernow’s recent biography of him. Fittingly, I’ll close with a quotation often attributed to Twain, though, as it turns out, there is no definitive evidence he said it.

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

We may not know with certainty who said this, but regardless of the source, it sure seems true to me.